DEALING WITH DIVERSITY

2.3 What I need to know in order to study the Bible story

2.3.1 Historical and social context

Check the following information, along with the map (see 3.3) and the summary table (3.2) with the protagonists, events and dates.

The story of the crossing of the Red Sea* can be found in the book

of Exodus* in the Old Testament*. This book includes the events that

took place around the 13th century BCE and reveal God’s intervention in

history with the aim of liberating the Israelites from the Egyptians and

leading them to the land of Canaan*. The Israelites lived in Egypt from

1600 to 1200 BCE, for approximately 400 years. When Ramses II* became

Pharaoh (1290–1224 BCE), he took strict measures against them, fearing

they would ally with other peoples of the desert and revolt against him. One

such measure was the killing of Jewish male children to limit their number.

Moses* was born at that time, and was miraculously saved from death. He

was chosen by God to liberate the Israelites and lead them to the land of

Canaan*.

The story of the crossing of the Red Sea* can be found in the book

of Exodus* in the Old Testament*. This book includes the events that

took place around the 13th century BCE and reveal God’s intervention in

history with the aim of liberating the Israelites from the Egyptians and

leading them to the land of Canaan*. The Israelites lived in Egypt from

1600 to 1200 BCE, for approximately 400 years. When Ramses II* became

Pharaoh (1290–1224 BCE), he took strict measures against them, fearing

they would ally with other peoples of the desert and revolt against him. One

such measure was the killing of Jewish male children to limit their number.

Moses* was born at that time, and was miraculously saved from death. He

was chosen by God to liberate the Israelites and lead them to the land of

Canaan*.

On their way to the land of Canaan*, the Israelites did not follow the

shorter, coastal route. Instead, in order to avoid the Egyptian guards,

they headed south to the Red Sea*. Pharaoh at that time was Merneptah*

(1224–1204 BCE), the successor of Ramses II*. With his army, Merneptah*

pursued the Israelites as far as the sea, but he could not prevent them from

fleeing, because God opened a passage for them through the sea. Marching

through the sea, they were able to proceed to the desert and were saved.

In commemoration of this important event, Israelites celebrate “Pesach*”

(=passage) even today, as the crossing of the Red Sea* marked their

passage from slavery in Egypt to freedom.

On their way to the land of Canaan*, the Israelites did not follow the

shorter, coastal route. Instead, in order to avoid the Egyptian guards,

they headed south to the Red Sea*. Pharaoh at that time was Merneptah*

(1224–1204 BCE), the successor of Ramses II*. With his army, Merneptah*

pursued the Israelites as far as the sea, but he could not prevent them from

fleeing, because God opened a passage for them through the sea. Marching

through the sea, they were able to proceed to the desert and were saved.

In commemoration of this important event, Israelites celebrate “Pesach*”

(=passage) even today, as the crossing of the Red Sea* marked their

passage from slavery in Egypt to freedom.

During this period, God makes a Covenant, i.e. a Testament* with His

people and at the same time protects them, supports them, cares for

them, strengthens and guides them. On the other hand, the people relate to

him, trust him and recognize him as unique and omnipotent.

During this period, God makes a Covenant, i.e. a Testament* with His

people and at the same time protects them, supports them, cares for

them, strengthens and guides them. On the other hand, the people relate to

him, trust him and recognize him as unique and omnipotent.

Protagonists

Event

Dates

Ramses II

Egyptian Pharaoh who took strict measures against the Israelites, fearing they could ally with peoples of the desert and revolt against the Egyptians.

1290–1224 BCE

Moses

Leader of the Israelites who led them to liberation from the Egyptians.

1393–1273 BCE

Merneptah

Egyptian Pharaoh. Son and successor of Ramses II. Pursued the Israelites with his army as far as the sea, but was unable to prevent their escape

1224–1204 BCE

2.3 MAP

2.4 The crossing of the Red Sea

Then the Lord said to Moses: 2 Tell the Israelites to turn back and camp in front of Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea […] 10 As Pharaoh drew near, the Israelites looked back, and there were the Egyptians advancing on them. In great fear the Israelites cried out to the Lord. […] 13 But Moses said to the people, “Do not be afraid, stand firm, and see the deliverance that the Lord will accomplish for you today; for the Egyptians whom you see today you shall never see again. 14 The Lord will fight for you, and you have only to keep still.” 15 Then the Lord said to Moses, “[…] Tell the Israelites to go forward. 16 But you lift up your staff, and stretch out your hand over the sea and divide it, that the Israelites may go into the sea on dry ground. 17 Then I will harden the hearts of the Egyptians so that they will go in after them; and so I will gain glory for myself over Pharaoh and all his army, his chariots, and his chariot drivers. 18 And the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord, when I have gained glory for myself over Pharaoh” […] 21 Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea. The Lord drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night, and turned the sea into dry land; and the waters were divided. 22 The Israelites went into the sea on dry ground, the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left. 23 The Egyptians pursued, and went into the sea after them, all of Pharaoh’s horses, chariots, and chariot drivers. […] 26 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, so that the water may come back upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots and chariot drivers.” 27 So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at dawn the sea returned to its normal depth. As the Egyptians fled before it, the Lord tossed the Egyptians into the sea. 28 The waters returned and covered the chariots and the chariot drivers, the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea; not one of them remained. 30 Thus the Lord saved Israel that day from the Egyptians; and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore. 31 Israel saw the great work that the Lord did against the Egyptians. So the people feared the Lord and believed in the Lord and in his servant Moses.

2.4.2 Exercises

In the following exercises, you can process the biblical text by identifying

words and phrases that show God to act violently and then to investigate

why the biblical writer presents God to be violent and vindictive.

Comprehension

Exercise 1

Which of the following adjectives would you use to describe the God you

encounter in the text?

Omnipotent

Biased

Vengeful

Angry

Violent

Forgiving

Evil

Benign

Harsh

Protector

Helper

Punishing

Intervening

Miraculous

Compassionate

Righteous

Saviour

Liberating

Exercise 2

Find and underline in the Bible text the phrases that show God’s wrath

towards the Egyptians.

Exercise 3

In the same text, mention sentences which show the reasons for God’s

violent actions.

Seeking for the deep interpretation

The biblical narration we read, describes a God who uses violence against

humans. Let’s read the following text and try to understand why the author

of the Bible presents God like this. Maybe we need to consider something

else?

God as an avenger

All the events of the Old Testament* were transmitted orally for centuries

before they began being recorded. These Oral Traditions* contained many

expressions of emotion and tension, which were often exaggerated, and today

we need to distinguish these from historical information. It’s not our aim to

discover what actually happened then, but to try to understand the significance

it had for the life of those people who recorded the events centuries later, with

the intention of proclaiming their faith in the one and only God. The one who,

when needed, was always present and saved them from harm, evil and death.

They were deeply convinced that they could not succeed on their own during

those dramatically difficult times. This does not mean (as understood by those

who interpret the Old Testament* literally) that God killed children or enemies

[...] Rather, it expresses their deep faith that, in this struggle, their lives and

rights were protected by God. With such a view, history becomes “sacred

history.” That is, when man recognizes Divine Providence in cases where life

is preserved, protected, and escapes the danger of extinction. And this Godsavior

of their lives is the one people trust.

(Ol. Grizopoulou & P. Kazlari, Old Testament, The prehistory of Christianity,

Class A Religious Education (Teacher’s book), Athens: Ο.Ε.D.V., undated, p.58)

Based on the fact that the recording of historical events by biblical writers

takes place many centuries after the events themselves, try to answer the

following questions:

To which extent are these events accurately described? Do they include

exaggerations because they serve other purposes? What are the purposes

of this record?

2.5 SO FAR...

… we have learned … understood … clarified

In the Old Testament*, the narration of the crossing of the Red Sea*

(Exodus* 14:1-31) contains scenes of violence. It is violence exercised by

God against the Egyptians, whom he eradicates, thus saving the people of

Israel from their persecutors. Approached literally, this narration describes

a God who is biased in favor of one particular nation and uses violence to

bring another one to destruction.

The core of the historical events of Exodus* took place around the 13th

century BCE; however, the relevant texts of the Old Testament* were

recorded much later, in the 6th to 5th century BCE. The motivation for

writing down narrations which had been passed down orally over centuries

was not the study of history (in the contemporary sense of an accurate,

objective understanding of events); but rather, it reflected concerns for

the significance these narratives could have for people at the time of their

recording. People of that era had already developed civilization, had settled

in cities and their living conditions were essentially different from those

of the period of the events narrated. Therefore, the references of the

Scriptures are not intended to provide exact historical information, as

we understand it today, but rather to elaborate eternal theological truths,

that will remain valid as long as there are people on Earth.

Biblical authors attempted to graphically illustrate, absolutely and leaving

no room for doubt, the omnipotence of the one and only God, in contrast to

the weakness or even the non-existence of the pagan deities of that time.

Thus, their goal was to emphasize that their God is a unique, omnipotent

protector and liberator. Every time they lived through difficult and dramatic

situations, he was present and saved them from every evil. Their profound

conviction was that they could not cope with the hardships of life on

their own, but God, through his saving interventions, protected their every

righteous struggle.

Approaching the narration of the crossing of the Red Sea*, as well as all

the narrations of the Old Testament*, from this perspective, we are able

to understand the significance they have for us today and distinguish

between the “sacred history” found in these texts and the objective history

describing actual events.

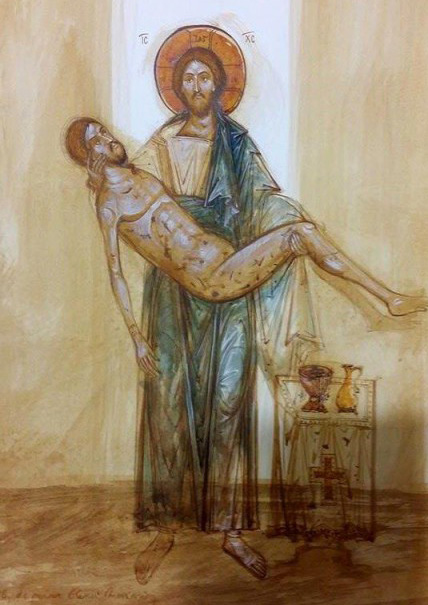

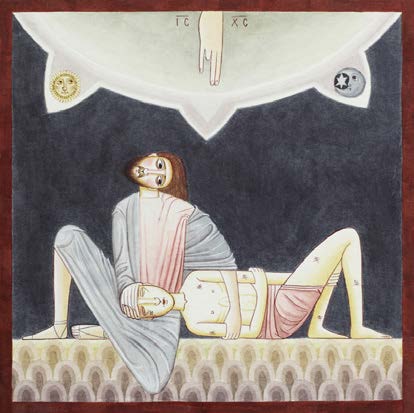

2.6 The image of true God

Through the following questions, taking the video and the text of the Old Testament* as a starting point, we can investigate the image of God the Father, a God of love for all.

2.6.1 Exercise 1

In the video, in the scene where Yiorgos chats with his mother about the

rescue of the refugees*, he asks “Mom, do you think God can do evil?”

to which she answers, “Since we call him Father, I cannot imagine him

harming his children.”

What can the phrase “God is Father” mean to a Christian?

In order to answer, we will use the following text from the New Testament*:

Speaking to his disciples, Jesus says: “You have heard that it was said,

‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love

your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those that hate you

and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your

Father in heaven; for he causes his sun to rise on both the evil and on the

good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous.” (Mt. 5:43-

45)

Answer:

“Father” means that:

2.6.2 Exercise 2

God is Father to all men. Why, then, when we feel fear of the stranger and

of the unknown, do we often need a strong God who protects only us and

annihilates the one we fear?

When we are afraid, our image of God, but also of our fellow humans, is

often affected by our insecurity. How can we deal with our fears towards

strangers? In the following paragraph, underline the keywords that answer

the above question. Explain your choice.

Let’s remember what we saw in the video: Yiorgos shares his father’s fear

of the supposedly “dangerous” refugees* and thus he remembers the story

of the Old Testament*. In the end, however, the youngsters’ contact and

acquaintance with the refugees* eliminates the fear and creates feelings

of friendship and familiarity with them.

2.6.2 Exercise 2

According to the Christian tradition, God is …

… Father, who loves all people with no exceptions and discriminations. God-

Father, being Love himself, calls all of us to love all of our fellow humans,

even our enemies, if we want to be his real children.

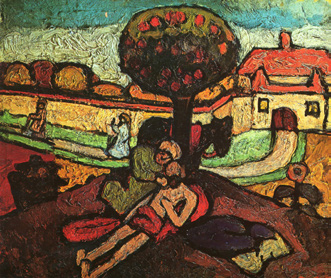

2.8 Additional Assignments: Material for further discussion

Figure 2.6

Marc Chagall, The

Crossing of the Red Sea,

1955

Figure 2.6

Marc Chagall, The

Crossing of the Red Sea,

1955

Exodus (Edith Piaf)

They left during the winter sun

They left running through the sea

To erase fear

To override fear

That life had nailed into the depths of their hearts

They left believing in the harvest

From the old country of their song

Their hearts singing with hope

Their hearts bellowing with hope

They have reclaimed the road of their memories

They have cried the tears of the sea

They have recited so many prayers

“Deliver us, our brothers!

Deliver us, our brothers!”

That their brothers will pull them towards the light

They are there in a new country

That floats with the mast of their boat

Their broken hearts of love

Their hearts of love lost

They have found the land of love

Figure 2.6

Marc Chagall, The

Crossing of the Red Sea,

1955

Figure 2.6

Marc Chagall, The

Crossing of the Red Sea,

1955

2.9 GLOSSARY

Clarification of theological terminology, and also information on the historic personalities and places found in the book.

Canaan

In the Old Testament, refers to the land settled by the Israelites, but also by its “Canaanite” inhabitants. The

name means “country of purple” (Greek name “Phoenicia”) and comes from the main export product of the

region, a substance used to dye fabrics deep purple. The land of Canaan is the Promised Land; the fulfillment

of God’s promises to the people of Israel by enabling them to settle in this area after leaving Egypt.

Easter (Christian)

Christians keep the same Jewish name for their own celebration, Easter, when they remember Jesus Christ,

who through His Crucifixion and Resurrection gave man the prospect of life, and freedom from death and

evil in all its manifestations. They celebrate the restoration of life in its entirety and its victory over death

which was brought by Jesus Christ.

features.

Exodus

The book of Exodus is the second book of the Bible and the Hebrew Bible and belongs to the historical books

of the Old Testament. Exodus, together with the books of Genesis, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy

is the Pentateuch (in Hebrew Law (Torah). In the Greek translation of the Septuagint (LXX) it was called

“Exodus”, because the central issue is the exit (ie the liberation) of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. The

protagonist in the Exodus is Moses.

Merneptah (1224-1204 BCE)

The 3rdson of Ramses II and his wife Isetnofret (and 13th son of Ramses, overall). With his army, Merneptah

pursued the Israelites to the sea, but was unable to prevent them from fleeing.

context than Mecca.

Moses

Charismatic personality of the Jewish nation and religion. Moses was a leader, a hero, a legislator, a prophet

and a mediator between God and his people. He led the people of Israel to liberation from the Egyptians,

crossing the Red Sea and through the Sinai Desert for 40 years. According to Jewish and Christian tradition,

Moses received the 10 commandments from God. He receives special honour as a prophet from both

Christians and Muslims.

Oral Traditions (Old Testament)

Words and narratives that Jews, both men and women, repeated to each other outside their tents in the

desert, and in their homes, whether hovels or palaces. At the heart of these narratives has always been the

conviction that God is the great protagonist in human life. Most of these narratives were transmitted in ways

that were easy to decipher: narratives, images, quotes, poems. In this way they were indelibly engraved in the

memory of people and everyone was able to understand them. Centuries later, these narratives began to be

recorded and gradually, a collection of texts was created that later became the Old Testament.

Pesach (Jewish)

The word Pesach means “passage”. Jews celebrating Pesach remember that their ancestors crossed the

Red Sea from slavery in Egypt into freedom.

Ramses II (1290-1224 BCE)

Also known as Ramses the Great. He was the third pharaoh of Egypt’s 19th dynasty and the most powerful

of all Egyptian rulers.

Red Sea

The narrow sea arm of the Indian Ocean between NE. Africa and SW. Asia, where it creates the ancient

Arabian Gulf. At the time of the “Exodus” of the Israelites from Egypt, the Red Sea was also called the

Sea of Reeds and was then a lake. The northern part, west of the Sinai Peninsula, is mentioned in the Old

Testament book of Exodus as being crossed by the Israelites since, for a millennium, it was crossed only

widthwise and never lengthwise.

Refugee

Someone who is forced, by circumstances or by violence, to leave his or her home or place of permanent

residence and seek refuge in a foreign country or country of ethnic origin. Often used in the plural to refer to

populations of people moving in groups.

Testament

The term literally means the last expression of a person’s will, but in the Bible it is used to describe a

Hebrew word meaning “treaty”, “alliance” or “agreement”. However, in addition to the meaning it can have

for human relationships, the term is used specifically to denote the particular agreement that governs

God’s relationship (Gen. 9:8; Ex. 15:18; 17:1) with the people of Israel (Ex. 19-24) and aims to create the

conditions for the salvation of all mankind. The responsibility for initiating the agreement lies with God, who

determines its content and terms. But this does not abolish the freedom of man, who is free to accept or

reject the agreement, which provides for rights and obligations for both God (faithfulness to promises, love

and protection for his people) and man (faith in the One and Only God, and social justice). Thus the covenant

does not define a God-master and man-slave relationship, but a father-son relationship (Ex. 4:22).

REFERENCES

The list of books used by the writers in the preparation of the book at hand, plus the works of art

and music used as stimuli for the students, along with the sources where they have been found.

Books

The Holy Bible, Old and New Testament, translated from the original texts, Athens: Hellenic

Bible Society, 1997 [Η Αγία Γραφή, Παλαιά και Καινή Διαθήκη, Μετάφραση από τα πρωτότυπα

κείμενα, Αθήνα: Ελληνική Βιβλική Εταιρία, 1997]

S. Agourides, History of the religion of Israel, Athens: Ellinika Grammata, 1995 [Σ. Αγουρίδης,

Ιστορία της Θρησκείας του Ισραήλ, Αθήνα: Ελληνικά Γράμματα, 1995]

Anastassios (Yiannoulatos) Archbishop of Tirana, Co-existance, Athens: Armos, 2016

[Αρχιεπισκόπου Τιράνων Αναστασίου (Γιαννουλάτου), Συνύπαρξη, Αθήνα: Αρμός, 2016]

J. Daniélou, Essai sur le mystère de l’histoire, Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1982 [J. Daniélou,

Δοκίμιο για το Μυστήριο της Ιστορίας, μτφρ. Ξ. Κομνηνός, Βόλος: Εκδοτική Δημητριάδος,

2014]

R. Debray, God. An itinerary (trns J. Mehlman), London & New York: Verso, 2004 [Ρ. Ντεμπρέ, Ο

Θεός: Μια ιστορική διαδρομή, μτφρ. Μ. Παραδέλη, Αθήνα: Κέδρος, 2005]

Ar. Emmanouil, Dictionary of Hebrew terms and names, Athens: Gavrielides, 2016 [Άρ. Εμμανουήλ,

Γλωσσάρι Εβραϊκών όρων και ονομάτων, Αθήνα: Γαβριηλίδης, 2016]

R. Girard, La violence et le sacré, Editions Grasset, 1972 [Ρ. Ζιράρ, Βία και θρησκεία: Αιτία ή

αποτέλεσμα; μτφρ. Α. Καλατζής, Εκδ. Νήσος, Αθήνα, 2017]

Ol. Grizopoulou – P. Kazlari, Old Testament, The prehistory of Christianity, Class A Religious

Education (Teacher’s book), Athens: The Greek Organization for Publication of School Books

(Ο.Ε.D.V.), not dated. [Ολ. Γριζοπούλου - Π. Καζλάρη, Παλαιά Διαθήκη, Η προϊστορία του

Χριστιανισμού, Θρησκευτικά Α’ Γυμνασίου, Βιβλίο Εκπαιδευτικού, Αθήνα: Ο.Ε.Δ.Β., χ.χ.]

A. Kokkos et al., Education through the Arts, Athens: Metechmio, 2011 [Α. Κόκκος κ.ά.,

Εκπαίδευση μέσα από τις Τέχνες, Αθήνα: Μεταίχμιο, 2011]

M. Konstantinou, The Old Testament, Deciphering the universal human heritage, Athens:

Armos, 2008. [Μ. Κωνσταντίνου, Παλαιά Διαθήκη, Αποκρυπτογραφώντας την πανανθρώπινη

κληρονομιά, Αθήνα: Αρμός, 2008]

Th. N. Papathanassiou, “Anthropology, Culture, Praxis” in S. Fotiou (ed.), Terrorism and Culture,

Athens: Armos, 2013 [Θ. Ν. Παπαθανασίου, «Ανθρωπολογία, πολιτισμός, πράξη», στο Σ. Φωτίου

(επ.), Τρομοκρατία και Πολιτισμός, Αθήνα: Αρμός, 2013]

Th. N. Papathanassiou (ed.), Violence, religions and culture, Synaxis 98 (2006) [Θ. Ν.

Παπαθανασίου (επ.), Η βία, οι θρησκείες και η πολιτισμικότητα, Σύναξη 98 (2006)]

W. Zimmerli, Grundriss der alttestamentlichen Theologie, Dritte, neu durchgesehene Auflage,

W. Kohlhammer, 1978 [W. Zimmerli, Επίτομη Θεολογία της Π. Διαθήκης, μτφρ. Β. Στογιάννου,

Αθήνα: Άρτος Ζωής, 1981]

L. Zoja, La morte del prossimo, Torino: G. Einaudi, 2009 (Greek translation Μ. Meletiades, Athens:

Itamos, 2011) [L. Zoja, Ο θάνατος του πλησίον, μτφρ. Μ. Μελετιάδης, Αθήνα: Ίταμος, 2011]

Dictionary of Modern Greek Language (https://bit.ly/305zcoE)

Works of art

Moses and the Hebrews crossing the Red Sea, pursued by Pharoah: Dura-Europos synagogue,

303 B.C., https://www.flickr.com/photos/24364447@N05/16425564146

Mark Chagall, The Crossing of the Red Sea, https://richardmcbee.com/writings/contemporaryjewish-

art/item/chagall-and-the-cross

Ivanka Demchuk, Crossing the Red Sea, https://www.etsy.com/listing/563765092/crossing-thered-

sea-original-print-on?ref=landingpage_similar_listing_top-2&pro=1&frs=1

Bartolo di Fredi, The Crossing of the Red Sea, Collegiate Church of San Gemignano, Italy, Fresco,

1356, https://www.christianiconography.info/Wikimedia%20Commons/redSeaBartolo.html

E. Marnay, E. Gold & P. Boone, «Exodus», (song), sung by Edith Piaf, https://safeyoutube.net/

w/45HE

James Pinkerton, Crossing the Red Sea, 2019, https://fineartamerica.com/featured/crossing-thered-

sea-james-pinkerton.html

Raphael Posterazzi, Moses Crossing The Red Sea (1483-1520), St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City,

https://remnantculture.com/wp-content/uploads/pillaroffire.jpg

Maria Yannakaki, Passage [Μαρία Γιαννακάκη, Πέρασμα] 2016, https://www.lifo.gr/guide/

arts/3614